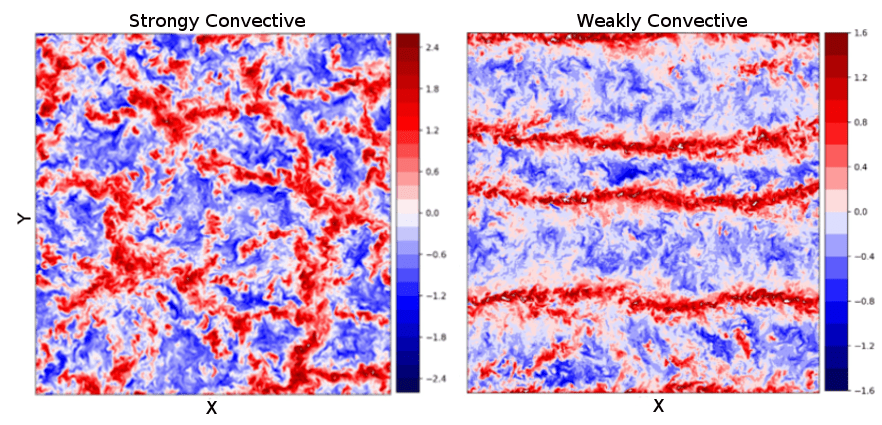

Numerous atmospheric processes exhibit diverse forms and structures, which can appear either random or organized. A key inquiry pertains to the influence of a physical process’s structure on its emergent impact or behavior. This question not only piques our scientific curiosity but also has significant implications for modeling physical phenomena. For instance, does organized convection leave a different footprint than random convection? The structural differences between roll and cell patterns in the convective boundary layer, as depicted in the image below, and their impact on the vertical mixing and flux of various quantities, such as heat, pollutants, and dust, is another example. Addressing these queries can provide valuable insights into the intricate workings of the atmosphere and facilitate the development of more accurate physical models.

Plot shows a horizontal cross section of vertical velocity in a (left) strongly convective, weakly sheared and (right) weakly convective, strongly sheared boundary layer, generated using large eddy simulation.

Weather and climate models that use a discretized representation of continuous equations approximate the impact of small-scale physics (which is smaller than the model’s grid) as a function of large-scale quantities (which are equal to or larger than the model’s grid). In doing so, the models generally ignore the structure of the unresolved physical processes. The question of whether or not we need to incorporate the missing piece of information regarding the structure of unresolved physical processes, as well as how to do so effectively, has not received an adequate response.

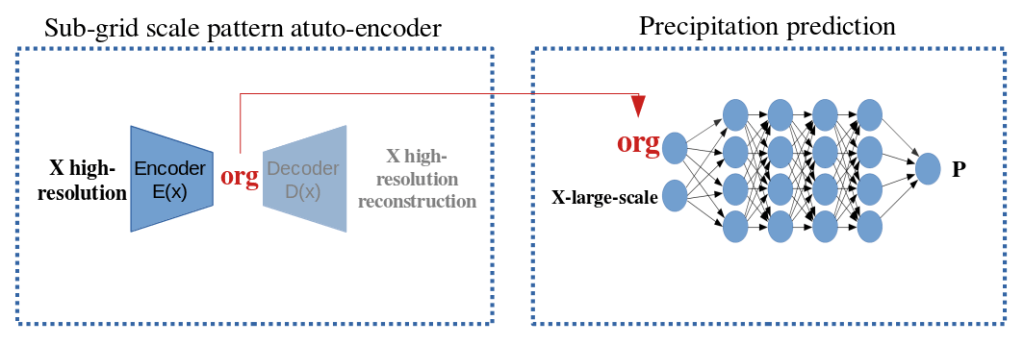

Machine learning algorithms are powerful tools that can help investigate both “whether” and “how” to effectively model sub-grid-scale structures. In our recent paper, we develop a novel neural network architecture to examine cloud organization and its impact on precipitation. Our network uses an auto-encoder to implicitly learn sub-grid-scale information relevant for predicting precipitation, which it then passes on to a feed-forward neural network. Our findings demonstrate that the latent representation of the auto-encoder effectively encodes sub-grid-scale information, leading to significantly improved precipitation predictions. Furthermore, building on this work, we investigate whether the sub-grid-scale structure also contains information that is relevant for predicting radiation.

Plot shows the architecture of the neural network: (left), an auto-encoder is applied to the high-resolution moisture field. (Right), the feed-forward network receives both large-scale variables and the latent representation of the auto-encoder to predict precipitation.

Our innovative neural network architecture, which employs two distinct machine learning tools to handle two scales – resolved and unresolved – is a groundbreaking approach with broad applicability. This architecture has the potential to revolutionize how we model and quantify complex two-field systems that require more than just mean or variance-based approaches. From studying the heat conductivity of ice sheets to representing land properties, the possibilities are endless..

Paper:

S.Shamekh et al ,PNAS (2023); Implicit learning of convective organization explains precipitation stochasticity